Architecture’s timeless journey: a Life of innovation and influence with Architect Francesco Soro

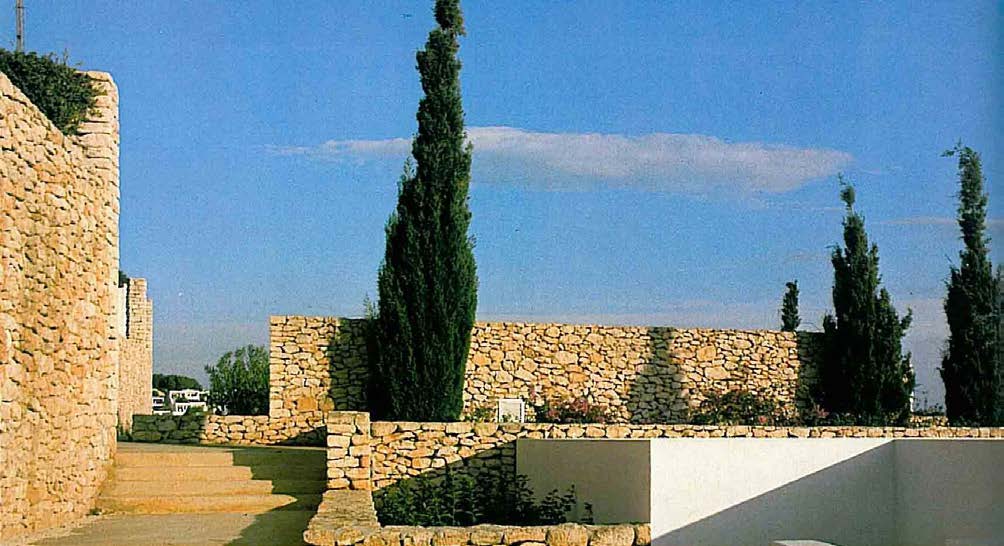

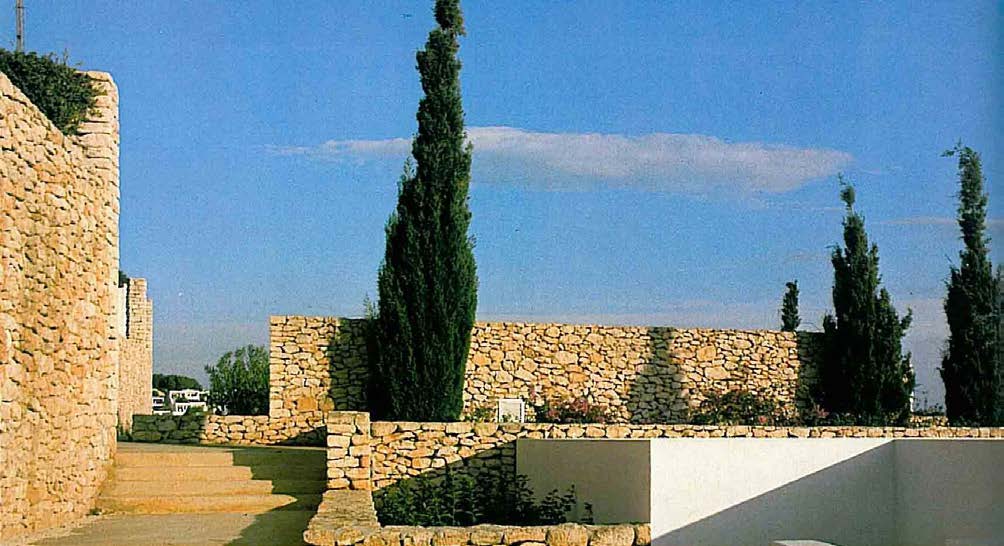

Your career, began in the ‘70s, and it has been marked by iconic and impactful projects such as Roca Llisa in Ibiza, the Biology building for the State University of Milan, and the tourist development in Calafell. What do you consider to be the main factors that have contributed to your enduring success and influence in the field of architecture and design? Additionally, among the many projects you have completed, is there one you feel particularly attached to and consider especially significant? Roca Llisa in Ibiza was where, at a young age, I began exploring creativity: organizing a display of volumes along the Mediterranean coast and selecting new materials.

I was especially captivated by the interplay between solids and voids, enhanced by the powerful sun creating shadows and greys. This Mediterranean approach formed the basis for future projects like San Roque in Cadiz, Golf in Calafell, Tarragona, a senior center in Jumilla, Murcia, a new settlement in Mogador, Morocco, urban development in Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, and La Misita in Agrigento. The same methodology influenced various designs, from large buildings to furniture. I look back with nostalgia on significant projects over 50 years in Architecture. Also The Biology Department at the University of Milan was a unique adventure: Magistretti and I participated in the Contract Competition with Meregaglia Company.

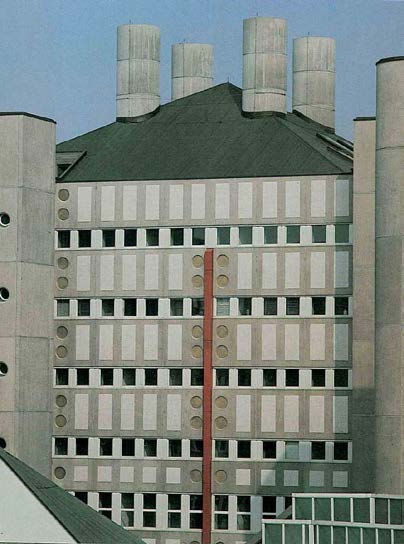

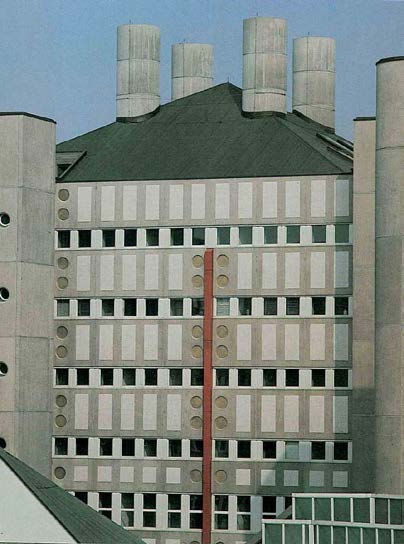

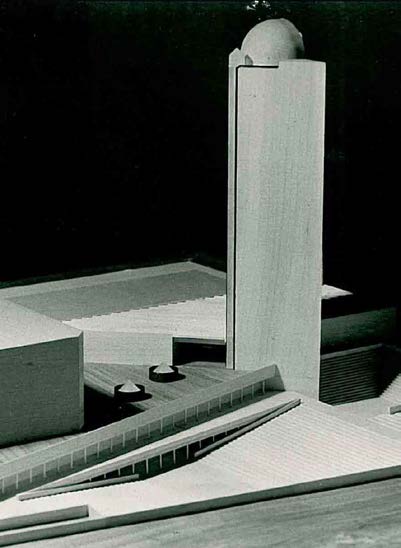

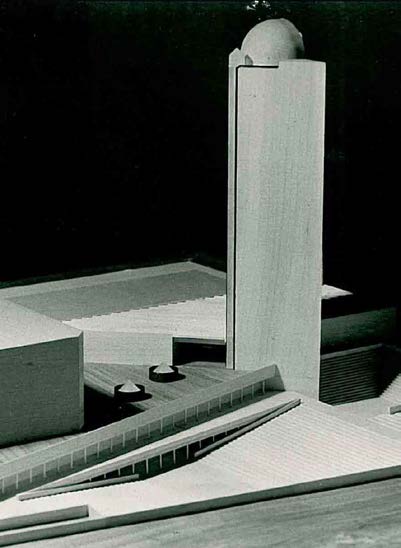

The theme was intriguing, and we quickly “sketched out” the idea. The building grew beside the Giuriati field, where I used to play rugby. We put gold on the facades, as the building represents culture, as we know culture is gold. Another enthusiastic bet was the New Policlinico of Milan proposal. Invited by the Lombardy Region, I suggested raising the intervention 15 meters above ground, creating underground access, and demolishing existing buildings to free the view of historic monuments like the Cà Granda. Passing by the hospital now, I see the buildings being reconstructed.

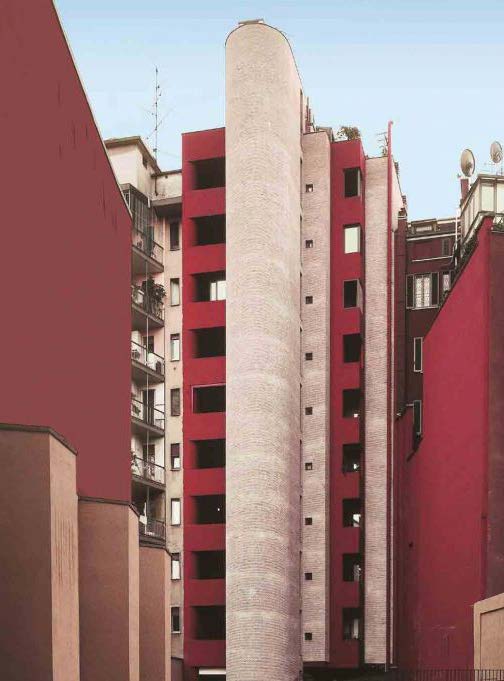

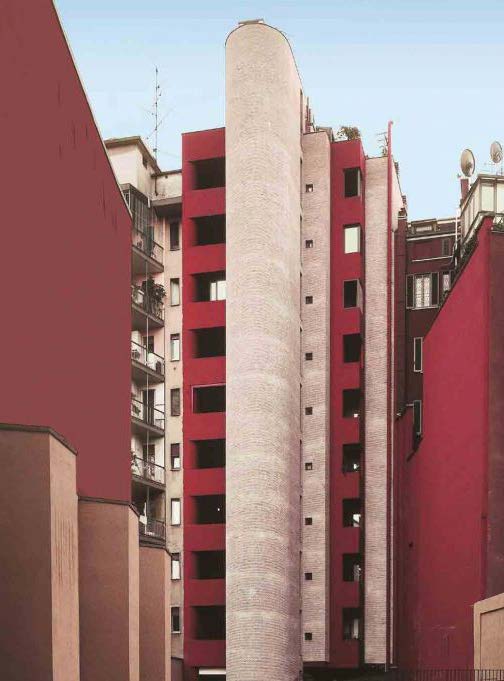

I didn’t presume to “teach how it’s done,” but at least I wanted to suggest an idea to preserve that historic Milanese presence. Always in Milan, I proposed a development for the Museum of Science and Technology: large spaces on the ground floor, while sections for “light” materials were housed in a tower with elevators, eliminating long walks for visitors. Another significant intervention was the Pini Hospital for rehabilitation in Via Isocrate. It was important to me to dress it with all the “Milanese-ness” it deserved. The terracotta brick cladding and discreet window openings protect and intimate it.

A large circular orange space on the first floor houses the bar, a gathering place for patients. The project I now feel most represented by is on Via Golgi in Città Studi in Milan, dedicated to the Faculties of Physics and Chemistry. Despite difficulties, including the location and lack of funds, the facade on Via Golgi stands out: about three thousand square meters of milky white glass block, allowing light in but preventing distractions. Supported by a peristyle of columns, it resembles a Greek temple.

Throughout your career, you have collaborated with some of the most prestigious names in design and architecture, and you have witnessed the emergence and development of trends that have characterized the last 50 years in the field. What has struck you most about the evolution of these fields in recent years, and how have you adapted to these changes? Could you share some reflections on how digitization, sustainability, and new technologies have influenced your work and your vision of design? As far as I am concerned, among other benefits, the major change in recent years has been saving space by moving from tables of 150×100 cm (or more!) to objects of 40×20 cm (PCs) and fabulous printers. On a practical and work level, the advent of new technologies has greatly facilitated the field of design and planning.

We have not let ourselves be seduced by the illusion of the “easy” that leads you by the hand to solve all problems (views, sections, axonometries, perspectives). No! We understood that before touching the wonderful mouse, one had to pick up the pencil again, prepare the machine and imagine the project seen from below, from above, and from all sides, exploded in space. COLLAGE represents a fusion of traditional craftsmanship and technological innovation, thanks to the collaboration with a former “workshop” that combines artisanal skills with modern industrial technologies.

As the founder of COLLAGE, can you tell us which aspect of this balance between tradition and innovation you find most stimulating and significant in creating products that meet the challenges of an increasingly competitive global market? Collage was my great passion, shared with my children during their free time, as we transformed old materials and explored new ideas. Through various craftsmen’s workshops, we created a collection that stands apart from contemporary trends. We repurposed humble materials like Masonite, turning them into high-quality items such as a sturdy table with a red base and a two-centimeter thick top finished with transparent polyester.

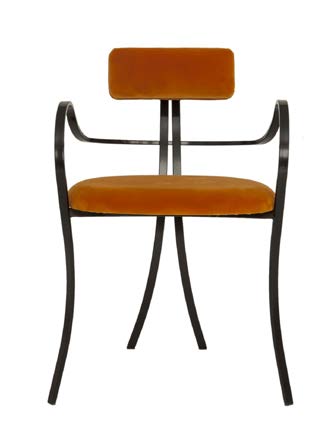

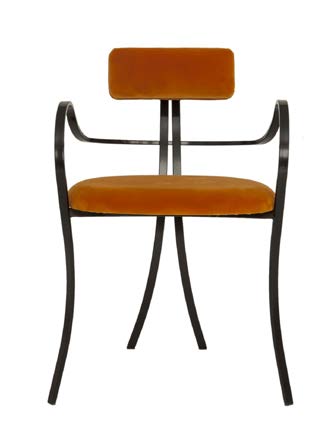

We revived the “Violet” chair from the early ‘90s and added practical features like a pocket to the Lilith armchair, to slip in the newspaper, the phone, the ball of yarn and knitting needles; it was well-received and I later saw it reproduced in other proposals! The Lilith armchair pays homage to my father’s work chair, with a redesigned backrest. The Tanit chairs, inspired by the goddess of Ibiza, are lightweight and handmade with metal frames, featuring customizable inlays of letters and figures for personalization. A series of these products adapted for hotel functions was also created, the Collage series for Hotels. Finally, to my great delight for my memories, they surprised me by reviving my “Compasso d’Oro” from 1981.

The historic Jonathan table series is enriched by coloring the metal structure of the base, especially in the low coffee table, worthy of being recognized as a “sculpture”. What I would gladly experiment with is imagining new objects conceived with new materials that technology is experimenting with. The “Compasso d’Oro” award for the sofa designed for Maddalena De Padova remains in history as a testament to your talent and excellence in the field of industrial design. How did the idea for this project come about, and what significance has it assumed in your career? The Siglo 20 sofa mentioned above was born from the same reflection read in point 3. At the end of the ‘70s, most of the seats were “modular” which left behind full and highly branded modular seats that echoed others.

I designed a volume of a Chesterfield, and when I saw the wooden structure of the prototype at the upholsterer, I decided to transform it into a rod, thus letting the upholstery “float”. We later studied a system to cast the visible iron structure. It was a surprise: some immediately called it High Tech, and Maddalena De Padova, out of caution, invented the slipcover to make it digestible to buyers by softening the aggressiveness of the “new”. In its 40 years of life, its “concept” has been revisited many times, but…